Three years ago, a 65-year-old morbidly obese woman came to the practice with a 30-40 year history of recurrent respiratory infections of both the lungs and sinuses. The infections had worsened over the last several years requiring several sinus surgeries and negatively impacted her quality of life. The patient had already been diagnosed with GERD (Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease), but additional findings included OSA (Obstructive Sleep Apnea) and IgG subclass 1 deficiency.

In 2017, despite addressing her OSA and the patient receiving IVIg therapy on a consistent basis, the patient was chronically on oral antibiotics and steroids for either a sinus infection, bronchitis or both. IgG total and subclass levels were all within normal limits and data from her CPAP showed excellent compliance. In addition, the patient stated that she was consistent with her proton pump inhibitor (PPI) which she took first thing in the morning.

Unfortunately, this is an all-too-common scenario that I face in my patient population; recurrent symptomatology despite adequate management of their underlying immunoglobulin deficiency. The $64,000.00 question is what’s missing? It is this question that frustrates not only the patient but many clinicians because they do not know what else to offer the patient.

It has been my experience that in many of these cases, it is that their GERD is what is not well-managed and that improvement in their management of it can improve their symptomatology.

GERD is a disease which is commonly known, but despite a significant amount of knowledge about the disease, diagnosis and management have been elusive. In many instances, clinical suspicion may be your greatest asset. From an infectious disease point of view, many times organisms that are found in the sinus cavities and sputum raise the concern over whether or not GERD is involved. Whenever I review respiratory (sinus or sputum) cultures where organisms such as Klebsiella, Pseudomonas or Enterobacter are seen, bells and whistles go off in my head that it may be a contributing factor in this particular patient’s disease process.

In many instances when I begin to talk about GERD with such patients, I usually get one of two responses: 1) I don’t have heartburn or 2) I do have GERD and take medication X daily. So why are you talking about something I either don’t have or I’m addressing?

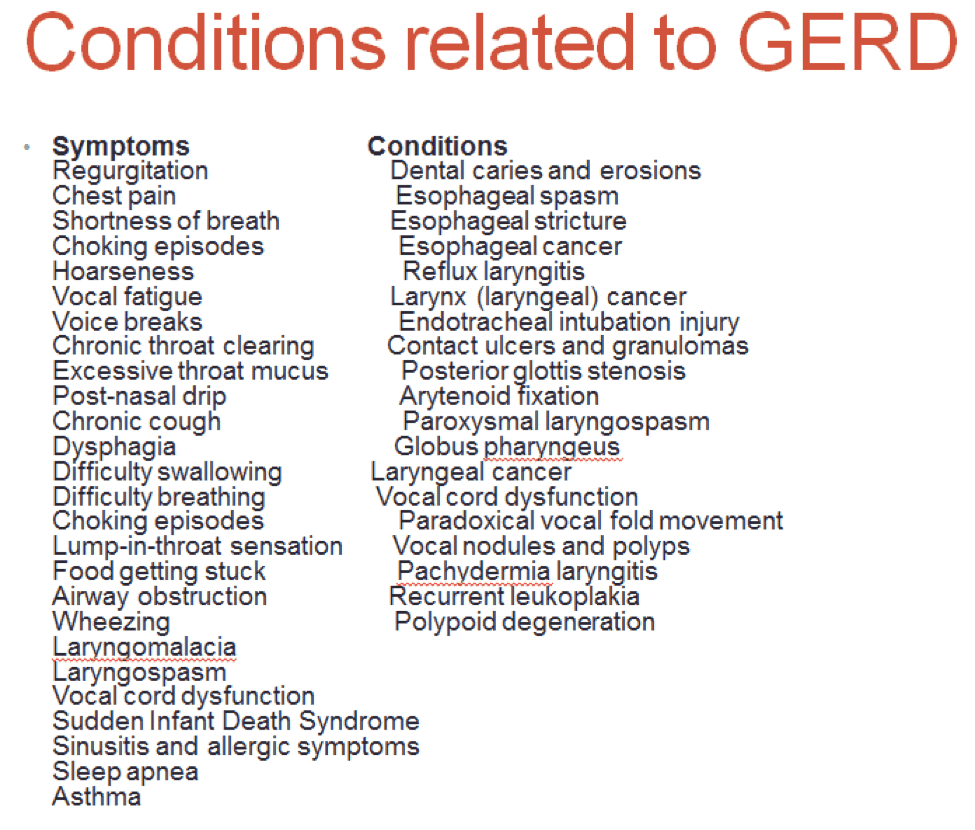

In response number 1, it has to be stated that not all patients with this can experience heartburn. In many instances, the only sign of the patient’s GERD may be an associated illness related to GERD such as sinusitis, asthma, COPD and recurrent cases of pneumonia. To be noted, there are many signs and symptoms that may not be thought to be related to GERD, which actually are related.

Patients with any of these signs or symptoms should be worked up.

The second response also needs to be addressed in that medication alone may not be enough in the management of GERD. The damage caused to the mucosa of the sinuses and lungs caused by GERD involves more than gastric acid alone. There are other caustic agents in the gastric secretions that can cause damage to mucosal membranes, specifically, pepsin. Pepsin is a digestive enzyme that is important in the breakdown of heavy proteins such as meat. It works very well in the stomach where it belongs due to the protective mechanisms of the stomach so that we don’t digest ourselves. However, problems occur when pepsin winds up in places it doesn’t belong, like the lungs or sinus cavities. If that enzyme can break down steak, imagine what it can do the mucosal linings of the sinuses and lungs if exposed.

Pepsin requires an acid environment in order to work well. Unfortunately, pepsin still has significant activity at pH of 4.5, so damage can occur to extra-gastrointestinal mucosa at a higher pH. Therefore, in cases where patients GERD are not well managed with PPI or other acid reducers such as ranitidine, suppressing gastric contents to the stomach alone becomes the key.

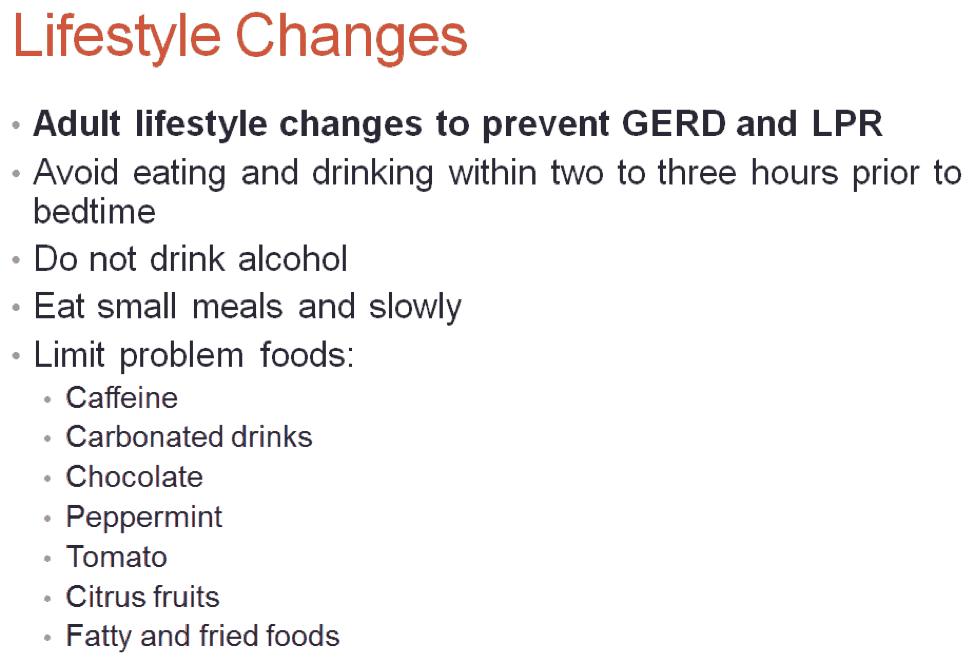

In order to do this, patients must employ lifestyle changes and in today’s society of instant gratification and the belief in instantaneous results, many would rather take more pills than change their lifestyles. Unfortunately, there is no way around the lifestyle changes, but the good news is once you become adherent to them, the quality of life will increase.

The lifestyle changes include Table 2.

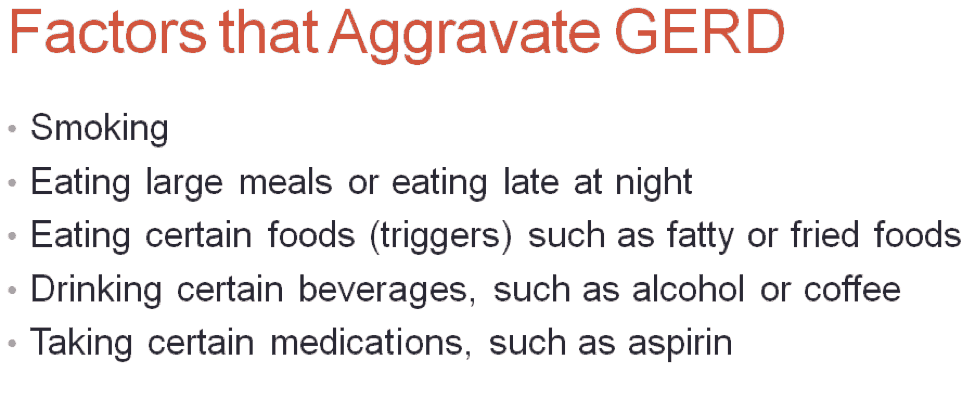

In addition, avoidance of certain triggers will help Table 3.

In the case of my patient though, she was extremely compliant with the lifestyle changes, unfortunately, she didn’t regard snacking after dinner while watching TV as eating. Apparently, my patient would constantly snack from the time she finished dinner until she went to bed. Amazingly, that was the only change she made and, in 2018, she has yet to be on antibiotics for either sinusitis or bronchitis. Additionally, she has lost close to 20 pounds to date.

Though this was a great achievement for this patient, in particular, I do have several patients that despite maximal medical management and a near Spartan approach to lifestyle changes, they are still extremely symptomatic. In these cases, surgery is the only option. This should only be used after all other options have been exhausted. Several of my patients that have had surgery are very pleased with the outcome.

The management of recurrent respiratory infections in most instances of these infections are multi-factorial and multi-faceted. In a patient who has both CVID and GERD, in order to achieve optimal management, both aspects must be addressed. Imagine, if you will, avoidance of respiratory infections is a well-spinning propeller, and CVID and GERD are the blades of the propeller. For that propeller to spin properly, both blades need to be equal and balanced; in other words, both need to be managed equally and properly.

This is a disease that everyone knows about, but it is a lot more complicated, both in diagnosis and treatments than both patients and some clinicians realize. However, once addressed properly, the outcome can be significant.